<<< Chapter Variants

B.1.1.7 ‘normalcy’

B.1.1.7 is now the new ‘normalcy’ in most European countries. It is about 50% more transmissible than historical strains and is expected to increase the basic reproductive number R0 by 0.3 to 0.4. In regions where R0 is only slightly below 1, a new surge of COVID-19 cases should be anticipated. Recent studies suggest that people infected with B.1.1.7 may have a more than 50% higher risk of hospitalization (Bager 2021) and death (NERVTAG 20210211, Davies 2021). B.1.1.7 is on its way to become the dominant global strain.

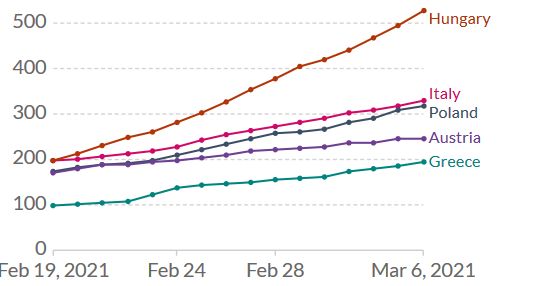

Figure 1. Increase of daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases over the last two weeks in selected European countries. Shown is the rolling 7-day average per million people. To recalculate these values as the ‘cumulative 7-day rolling incidence per 100.000 people’, multiply the values by 0.7. Example: the March 6 value for Italy, 328, is equivalent to a cumulative 7-day incidence of 230/100.000 people. Source and copyright: Our World in Data, accessed 7 March.

In these unfortunate circumstances, two pieces of good news stand out. First, lockdowns like those enacted in the UK, Ireland and Portugal are sufficient to control the spread of B.1.1.7. Second, B.1.1.7 does not substantially interfere with natural (see Dan 2020) or vaccine-induced immunity. Real-life data from Israel demonstrate that the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was highly effective even in a situation where B.1.1.7 was the dominant lineage. In a trial involving 596,618 vaccinees, the estimated effectiveness 7 days after the second dose was 92% for documented infection, 94% for symptomatic COVID-19, 87% for hospitalization, and 92% for severe COVID-19. Vaccine effectiveness started even two weeks after the first dose (Table 1). Likewise, data coming in from Scotland and in England suggest that even a single vaccine dose – Pfizer-BioNTech or AstraZeneca – protected well over 80% of vaccinees against COVID-19 related hospitalization at 28-34 days post-vaccination, even those aged ≥80 years (Vasileiou 2021, Hall 2021, Public Health England 20210222).

| Table 1. Estimated vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 outcomes a) 14 to 20 days after the first dose; b) 21 to 21 days after the first dose; and c) 7 days after the second dose. Adapted from Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting. NEJM February 24, 2021. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2101765 | |||||

| Period | Documented Infection | Symptomatic COVID-19 | Hospitalization | Severe Disease | Death |

| 14 to 20 days after first dose | 46% | 57% | 74% | 62% | 72% |

| 21 to 27 days after first dose | 60% | 66% | 78% | 80% | 84% |

| 7 days after the second dose | 92% | 94% | 87% | 92% | NA |

However, in most countries, COVID-19 vaccines will have no impact on the imminent B.1.1.7 wave. Countries unable to vaccinate the adult population within the next weeks will see a surge of COVID-19 cases, annihilating every prospect of a ‘normal’ Easter vacation. Countries unable to vaccinate their population before June will not see a normal summer season either. Finally, countries unable to vaccinate well over 80% of their population (vaccine skepticism, limited access, etc.) will struggle to return to pre-COVID-19 normalcy.

B.1.351-like variants

B.1.351-like variants are those with a high potential for evasion of natural or vaccine-induced immunity. They currently include B.1.351 (first detected in South Africa) and P.1 (Brazil). Both strains harbor the E484K (“Erik”) mutation (Tegally 2020, Voloch 2020). A map of all amino acid mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain (RBD) showed that the site where mutations tend to have the largest effect on antibody-binding and neutralization is E484 (Greaney 2021b). Recently, sera from B.1.351-infected patients have been shown to maintain good cross-reactivity against historical viruses (viruses from the first wave) (Cele 2021). Sera from B.1.351-infected patients would also seem to neutralize the P.1 (Moyo-Gwete 2021). If these data are confirmed, vaccine manufacturers working on a B.1.351 vaccine are on the right track.

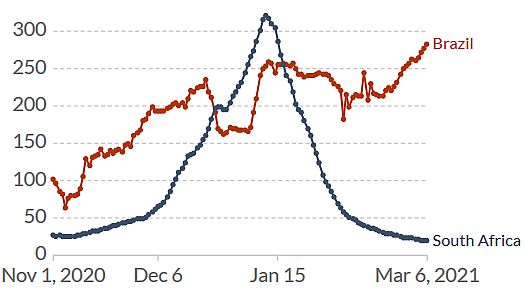

While the epidemiological situation in South Africa (B.1351) is currently under control, in Brazil it is not (Figure 2). The P.1 variant (Faria 2021, Naveca 2021) which arose first in November created a huge spike of coronavirus cases in the Northern Brazilian state of Amazonas around Manaus, replacing the historical lineage in less than two months. It is now spreading around the country.

Figure 2. Increase of daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases over the last two weeks in Brazil. Shown is the rolling 7-day average per million people. To recalculate these values as the ‘cumulative 7-day rolling incidence per 100.000 people’, multiply the values by 0.7. Example: the March 6 value for Italy, 283, is equivalent to a cumulative 7-day incidence of 198/100.000 people. Source and copyright: Our World in Data, accessed 7 March.

P.1 is refractory to multiple neutralizing monoclonal antibodies and more resistant to neutralization by (first-wave) convalescent plasma (de Souza 2021, Wang P 2021). Five months after booster immunization with the Chinese CoronaVac vaccine, plasma from vaccinated individuals failed to efficiently neutralize P.1 lineage isolates (de Souza 2021). In a pre-print paper, P.1 has been estimated to be 1.4–2.2 times more transmissible and able to evade 25-61% of protective immunity elicited by previous infection with non-P.1 lineages (Faria 2021). These data need to be confirmed.

Vaccines against variants

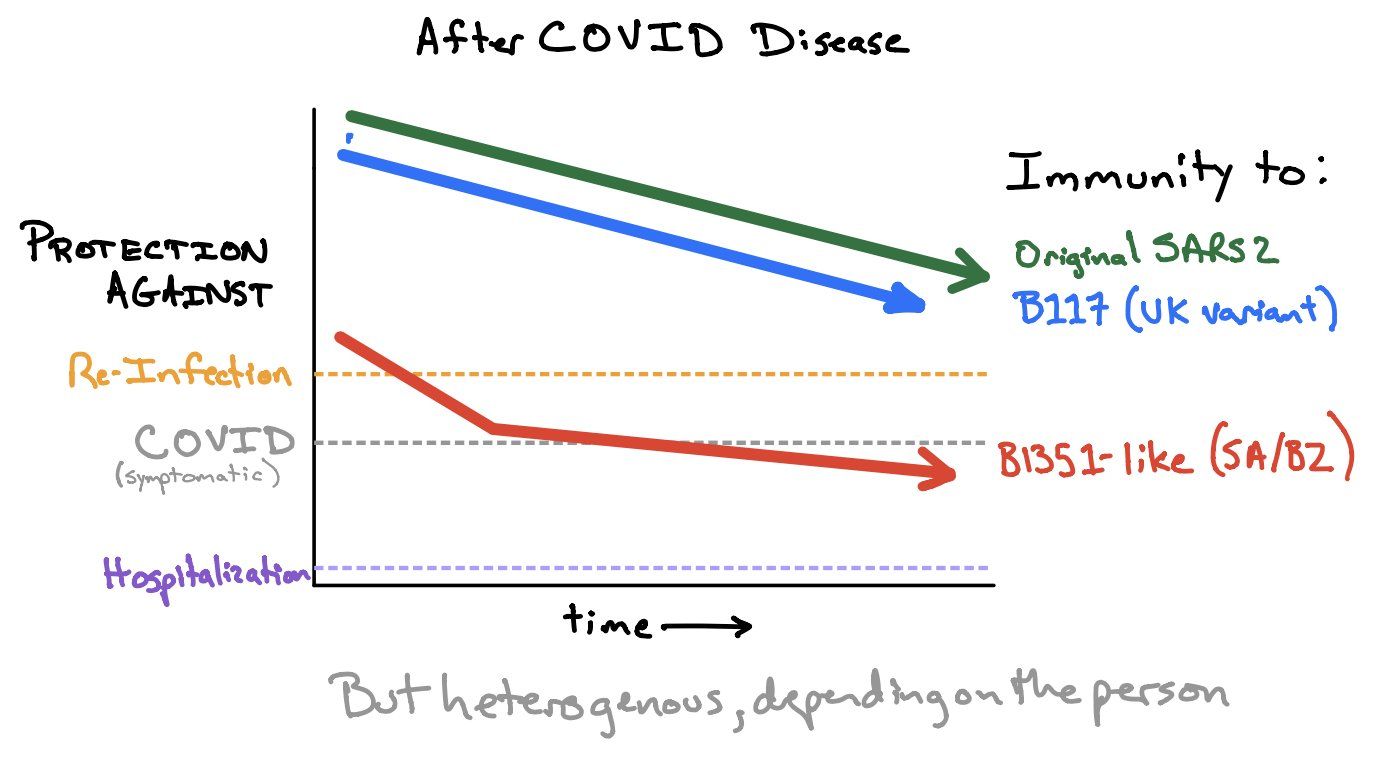

The current – preliminary – state-of-knowledge has been summarized in the Figure of the Week twittered by Shane Crotty (Figure 3; if you don’t follow Shane, start following him now: https://twitter.com/profshanecrotty). Data from in vitro and clinical studies suggest that natural and vaccine-induced immunity should protect against infection with B.1.1.7, but may be insufficient to protect against B.1.351 and P.1. However, even in the absence of antibody neutralization, we could expect some T cell protection (Tarke 2021). And while circulating memory T cells may not be effective in preventing Sars-CoV-2 infection, they can be expected to reduce Covid-19 severity. In summary (adapted from Shane Crotty, https://bit.ly/3uUXmPX):

- B.1.351-like strains (B.1.351, P.1 and future similar variants) must be taken seriously

- Several vaccines may provide satisfying immunity against those variants

- Most of the vaccines will probably provide excellent protection against hospitalizations/deaths from those variants

- A booster vaccine against those variants is likely to be highly effective

Figure 3. How much immunity do we need to protect against (asymptomatic) re-infection, symptomatic COVID and hospitalization. Source and copyright: Shane Crotty, https://bit.ly/3uUXmPX, March 4.